Congress leader Rahul Gandhi has escalated a political flashpoint by accusing the Election Commission of India (ECI) of enabling “vote theft,” claiming large-scale manipulation of voter rolls and erasure of evidence—yet much of the counter-firepower in public discourse has come from the BJP, not the Commission itself, sharpening questions over institutional neutrality and political overreach in defending a constitutional body.

The ECI has since issued a formal rebuttal and even demanded a signed declaration or an apology from Gandhi, but the ruling party’s rapid, aggressive counter-narrative has dominated prime-time debates and social feeds, reinforcing the perception that the Commission’s defence is being politically fronted.

What Gandhi Alleged — And Why It Landed

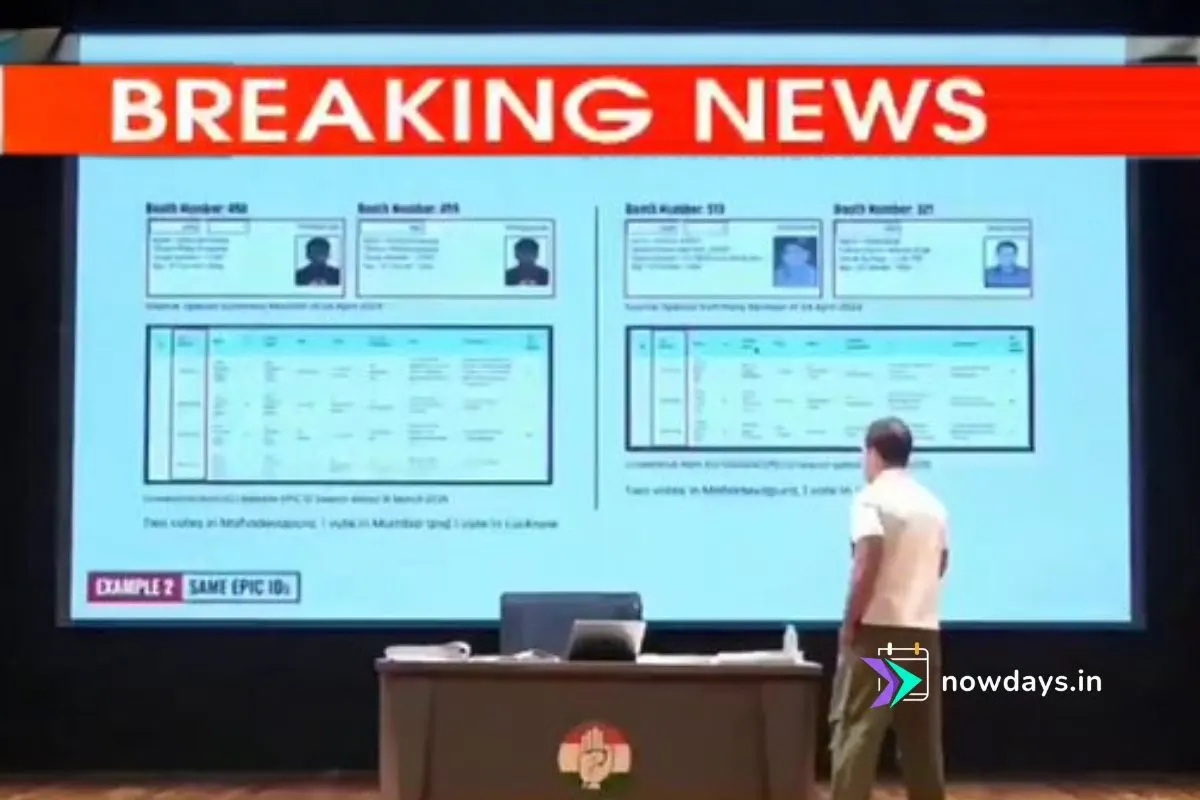

At successive briefings and a Bengaluru rally, Gandhi alleged the ECI colluded to “steal” the 2024 mandate by enabling fake and duplicate entries, withholding machine-readable electoral rolls, and limiting CCTV retention to stymie scrutiny—highlighting a case study of alleged 100,250 “fake votes” in the Mahadevapura Assembly segment under Bangalore Central. He framed five questions to the ECI on data access, CCTV deletion, roll tampering, intimidation, and whether the poll body is acting as an “agent” of the BJP, demanding transparent, machine-readable voter lists for independent audits.

LIVE: Press Conference – #VoteChori | Indira Bhawan, New Delhi https://t.co/BlZwacZpto

— Rahul Gandhi (@RahulGandhi) August 7, 2025

#VoteChori हमारे लोकतंत्र पर Atom Bomb है। pic.twitter.com/jcLvhLPqM6

— Rahul Gandhi (@RahulGandhi) August 7, 2025

Vote Chori सिर्फ़ एक चुनावी घोटाला नहीं, ये संविधान और लोकतंत्र के साथ किया गया बड़ा धोखा है।

— Rahul Gandhi (@RahulGandhi) August 8, 2025

देश के गुनहगार सुन लें – वक़्त बदलेगा, सज़ा ज़रूर मिलेगी। pic.twitter.com/tR7wh589fN

Gandhi’s camp circulated examples like “80 registered voters in a 120 sq ft room,” claiming the anomalies cost seats, while urging the Karnataka government to probe the Mahadevapura rolls independently if the ECI would not act. The wider thrust: without OCR-friendly rolls and defined data retention, citizens cannot meaningfully verify electoral integrity, creating a democratic deficit.

The ECI’s Response — Legalistic, Not Political

The ECI broke its usual reserve with a multi-point social rebuttal under the tag “ECIFactCheck,” labeling Gandhi’s claims “misleading,” citing Supreme Court precedent to justify denial of machine-readable rolls, and insisting proper legal routes—appeals, election petitions—exist and were scarcely used by the Congress during LS-2024 roll preparation. It argued CCTV/webcast footage is retained when petitions are filed; otherwise prolonged storage risks privacy and serves no legal purpose, offering a striking scale argument: reviewing footage from 100,000 booths would take 100,000 days with “no legal outcome” if not part of a case record.

The Commission publicly asked Gandhi to either file specific objections with a signed declaration as per Rule 20(3)(b) of the Registration of Electors Rules, 1960—or apologise—while noting previous communications to allied complainants that Gandhi later claimed did not exist. It reiterated that Karnataka’s own Congress-led government validated the same rolls by adopting them as the base for a caste survey, undercutting the charge of systemic roll fraud.

BJP Leads The Counterattack — And Frames The Narrative

Even as the ECI moved to rebut, BJP leaders filled the airwaves, branding Gandhi a habitual “liar,” accusing him of undermining institutions, and daring him to take the matter to court with an affidavit-backed submission. Television debates amplified the BJP’s framing: that Gandhi refuses due process but seeks to delegitimise a constitutional body in the public square, and that his “atom bomb” lacks admissible proof without sworn attestations. BJP-aligned commentary also argued that Gandhi inadvertently endorses the ECI’s ongoing Special Intensive Revision (SIR) by spotlighting duplicate voters—an exercise some opposition parties have resisted elsewhere.

This juxtaposition—BJP’s political blitz outpacing procedural ECI messaging—has reinforced the opposition’s charge that defences of the Commission are being politically mediated, even as the ECI insists on formal complaint mechanisms rather than media trials.

The Core Disputes: Data, Procedure, Evidence

- Machine-readable rolls: The ECI cites a 2019 Supreme Court rejection of an INC plea for machine-readable rolls as rationale for current practice, inviting formal objections instead of broad-brush allegations. Gandhi’s camp argues OCR-blocking formats make citizen audits impractical and that transparency demands modern, analyzable data formats.

- CCTV retention: Gandhi claims the ECI “destroys evidence” by limiting retention to 45 days absent a legal challenge; the ECI says extended retention absent petitions risks privacy and yields no legal remedy, urging use of election petitions to trigger preservation duties.

- Specificity and oath: The ECI and state CEOs in Karnataka, Maharashtra, and Haryana have asked Gandhi to sign declarations for named cases to proceed, including the Mahadevapura dataset; Gandhi counters that his parliamentary oath suffices and that the ECI is ducking substance with procedural hurdles.

- Fact claims contested: Media reports show some Gandhi-cited datapoints—like multi-state EPIC duplication claims—being challenged or found unsubstantiated by fact-checkers, further fueling the BJP’s accusation of “baseless” assertions.

Expert and Legal Views: Transparency vs. Traceability

Election-law experts on news panels note that while Gandhi’s questions on data accessibility and retention are legitimate in a digital era, the ECI’s insistence on statutory pathways is equally grounded: claims must be particularised, sworn, and filed to trigger investigatory and evidentiary processes. Transparency advocates argue that proactive release of machine-readable rolls—alongside privacy safeguards—would reduce conspiracy cycles and shift the burden from litigants to open data norms, especially when parties seek to audit at scale.

Institutional analysts warn that a political party fronting the public defence of the Commission risks blurring lines between the state and the incumbent, even if the Commission is responding in parallel through official channels. The optics matter: when political surrogates dominate the narrative, institutional credibility can suffer, regardless of legal correctness.

What Happens Next

- Affidavits or PILs: If Gandhi files signed, specific objections naming voters and precincts, he can compel fact-finding and evidentiary retention; absent that, expect the ECI to hold its line and the BJP to continue the political defence.

- State-level probes: Karnataka could pursue an administrative audit of Mahadevapura rolls to test Gandhi’s claims in a controlled setting, potentially surfacing a replicable methodology for other seats.

- Policy debate on data: The controversy may reignite calls for machine-readable voter rolls with privacy protections, and for standardised CCTV retention policies tied to potential disputes, balancing transparency with legal process.

For now, Gandhi’s exposé has pushed the ECI into an unusually public rebuttal while the BJP prosecutes the political case on television and social media—precisely the dynamic fueling the headline claim that a constitutional body’s defence is being carried, in the public square, more by the ruling party than by the institution itself.