(New Delhi, July 31, 2025) – The label “golden period” resonates powerfully in Indian political discourse, often evoking nostalgic visions of prosperity, harmony, and national progress.

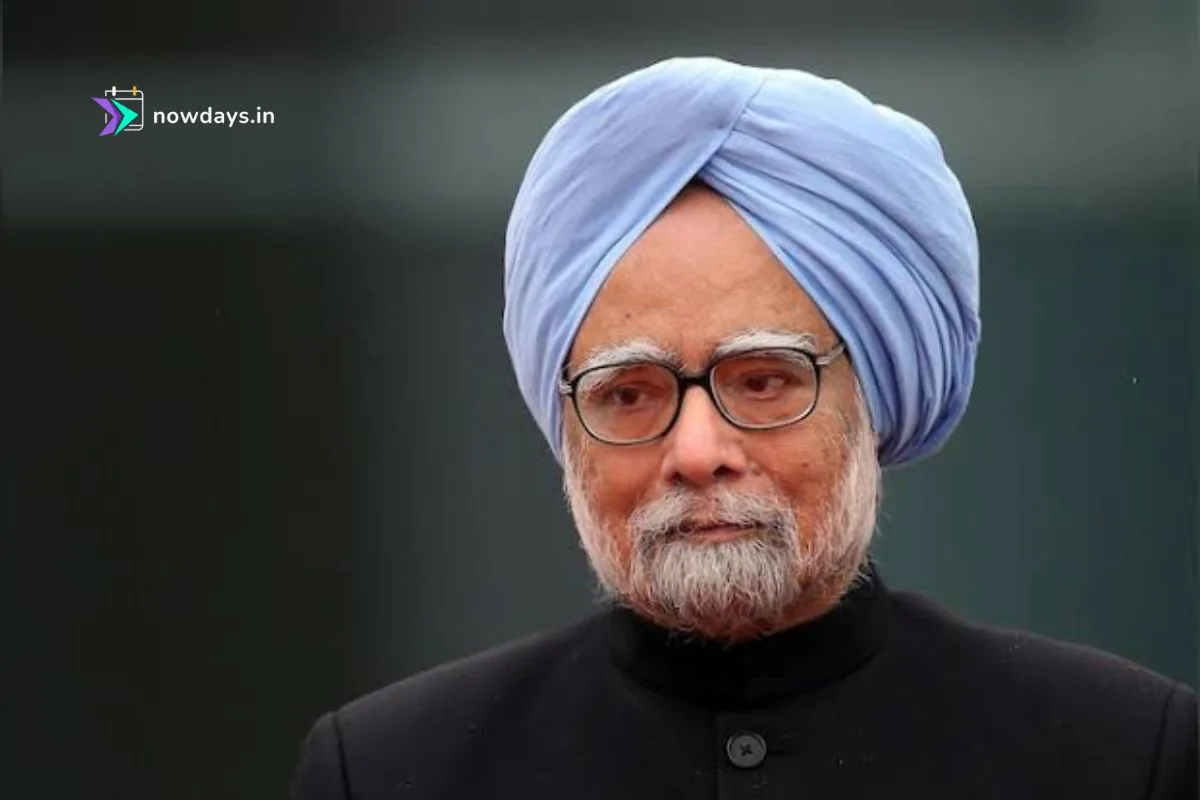

The decade spanning 2004 to 2014 – coinciding largely with the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) governments under Prime Minister Dr. Manmohan Singh – is frequently cited by its proponents as such an era. However, a closer examination reveals a far more complex picture, challenging the simplistic notion of a historical “golden age” and forcing us to confront the inherent contradictions within this timeframe. As historian D.N. Jha aptly argued, India never truly had a monolithic golden age; its history is instead a tapestry woven with threads of achievement and persistent struggle .

The Allure: Pillars of the “Golden Period” Narrative

- Economic Acceleration & Resilience: This period witnessed consistently high GDP growth rates, averaging around 7-8%, propelling India into the ranks of the world’s fastest-growing major economies. Landmark initiatives like the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA, later MGNREGA) aimed to provide crucial social security and stimulate rural demand, hailed as a major anti-poverty intervention . India navigated the devastating 2008 Global Financial Crisis with relative resilience compared to Western economies, bolstering its international economic standing.

- Legislative Landmarks: Significant rights-based legislation was enacted. The Right to Information Act (2005) empowered citizens and aimed to increase governmental transparency. The Forest Rights Act (2006) sought to address historical injustices against tribal communities. The Right to Education Act (2009) mandated free and compulsory education for children.

- Foreign Policy & Soft Power: The landmark Indo-US Civil Nuclear Deal (2008) marked a strategic shift, ending India’s nuclear isolation and deepening ties with the US. India’s global profile rose, reflected in its hosting of major international events and the growing influence of its cultural exports.

- Sectoral Boom – Legacy of the Golden Revolution: The momentum from the preceding horticulture-focused Golden Revolution (1991-2003) continued, solidifying India’s position as the world’s second-largest producer of fruits and vegetables. The National Horticulture Mission (NHM, launched 2005-06) significantly boosted production, increasing the area under horticulture from 11.72 million hectares (2005) to 23.2 million hectares (2015-16) and production from 150.73 million tonnes to 281 million tonnes – a testament to planned investment in the sector .

The Tarnish: Challenges Undermining the “Golden” Glow

- Jobless Growth & Persistent Inequality: Critically, the impressive GDP growth failed to generate sufficient formal employment opportunities. The benefits of growth were disproportionately captured, leading to widening income inequality and failing to lift vast sections of the population out of vulnerability despite poverty reduction. The “trickle-down” effect proved inadequate.

- Institutional Erosion & Mega Scandals: The latter half of the decade was marred by unprecedented corruption scandals (2G spectrum allocation, Commonwealth Games, coal block allocations) causing massive losses to the exchequer and severely damaging public trust in institutions. Policy paralysis often gripped the government in its second term.

- Social Unrest & Security Concerns: Persistent agrarian distress manifested in farmer suicides. Communal tensions and major terrorist attacks (like the 26/11 Mumbai attacks in 2008) exposed significant internal security challenges. The horrific Nirbhaya gang rape (2012) became a searing symbol of the urgent, unaddressed crisis of women’s safety.

- Inflationary Pressures: High inflation, particularly in food prices, eroded the purchasing power of ordinary citizens, especially impacting the poor and middle class, counteracting some gains from welfare schemes.

- The Myth of the Monolithic Golden Age: Historians like D.N. Jha consistently challenge the very concept of a historical “golden age” in India, arguing that such narratives obscure persistent social hierarchies, exploitation, and conflict throughout history . Applying this label to 2004-2014 risks similar oversimplification, ignoring its deep-seated problems. As Jha stated, “The history of India, like that of any other country, has been a story of social inequities, exploitation of the common people, religious conflict, and so on. The idea of a golden age has always been abused” .

The 2004-2014 Paradox: Promise vs. Reality

| Area | Achievements & Progress | Persistent Challenges & Failures |

|---|---|---|

| Economy | High GDP growth (~7-8% avg); MGNREGA launch; NHM success; Resilience during 2008 crisis | Jobless growth; Widening inequality; High inflation (esp. food); Policy paralysis (UPA-II) |

| Governance | RTI Act (transparency); FRA (tribal rights); RTE Act | Mega corruption scandals (2G, Coalgate, CWG); Institutional weakening |

| Social Welfare | Rights-based legislation framework; Poverty reduction (incomplete) | Inadequate healthcare access; Farmer distress/suicides; Nirbhaya case (safety failure) |

| National Standing | Indo-US Nuclear Deal; Rising global profile; Soft power | Persistent internal security threats (26/11, terror); Communal tensions |

A Complex Decade, Not a Gilded Age

Labeling 2004-2014 as India’s unequivocal “golden period” is an exercise in selective memory and political framing. It was undoubtedly a decade of significant economic momentum, landmark legislative initiatives, and enhanced global visibility. The fruits of the earlier Golden Revolution matured, and the NHM drove horticulture to new heights .

However, it was equally marked by profound failures: the disconnect between GDP growth and job creation, institutional decay through corruption, unaddressed agrarian and social crises, alarming inflation, and tragic security lapses. These flaws are not mere blemishes; they are fundamental contradictions that prevent the application of the “golden” label in any meaningful historical sense.

History, as D.N. Jha reminds us, resists simplistic categorization into golden or dark ages . The 2004-2014 decade exemplifies this complexity. It was a period of ambition, achievement, and undeniable progress in specific sectors, but also one of significant missed opportunities, unfulfilled promises for the majority, and systemic weaknesses laid bare.

Acknowledging both facets is crucial for an honest assessment. Rather than seeking a mythical past golden age, the focus should remain on building a future that delivers sustainable, equitable growth and genuine social progress for all Indians – a goal that transcends any single decade or political era. The true “golden period,” if achievable, lies ahead, demanding continuous effort to overcome the deep-rooted inequities that have characterized much of India’s long history.